Wildfires

At least 86 people have died in the devastating California wildfires. Large fires have grown in populated areas of California over the past few weeks, including the Camp Fire, north of Sacramento, the Woolsey Fire and the Hill Fire, northwest of Los Angeles.

The fires have destroyed thousands of structures and sent people fleeing. The Camp Fire has become the state’s most destructive blaze in at least a century. At least 560 people are missing in Northern California. The Camp Fire, which has burned 153,336 acres, was 85% contained as Nov. 21. Officials said they expect the fire to be fully contained by Nov. 30.

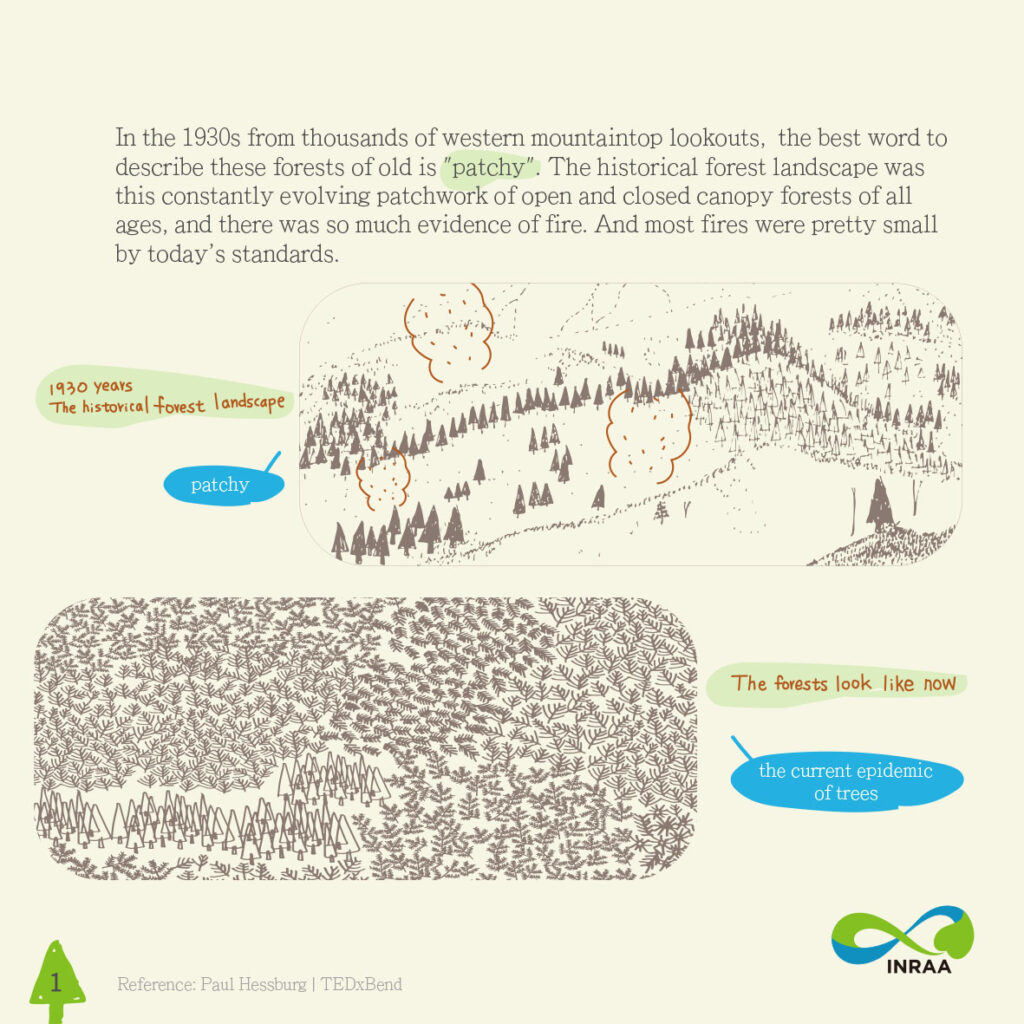

According to a studying from Paul Hessburg—a resarch ecologist in western United States, he thought the best word to describe these old forests in 1930s is “patchy.” The historical forest landscape was this constantly evolving patchwork of open and closed canopy forests of all ages, and there was so much evidence of fire. And most fires were pretty small by today’s standards. And it’s important to understand that this landscape was open, with meadows and open canopy forests, and it was the grasses of the meadows and in the grassy understories of the open forest that many of the wildfires were carried.

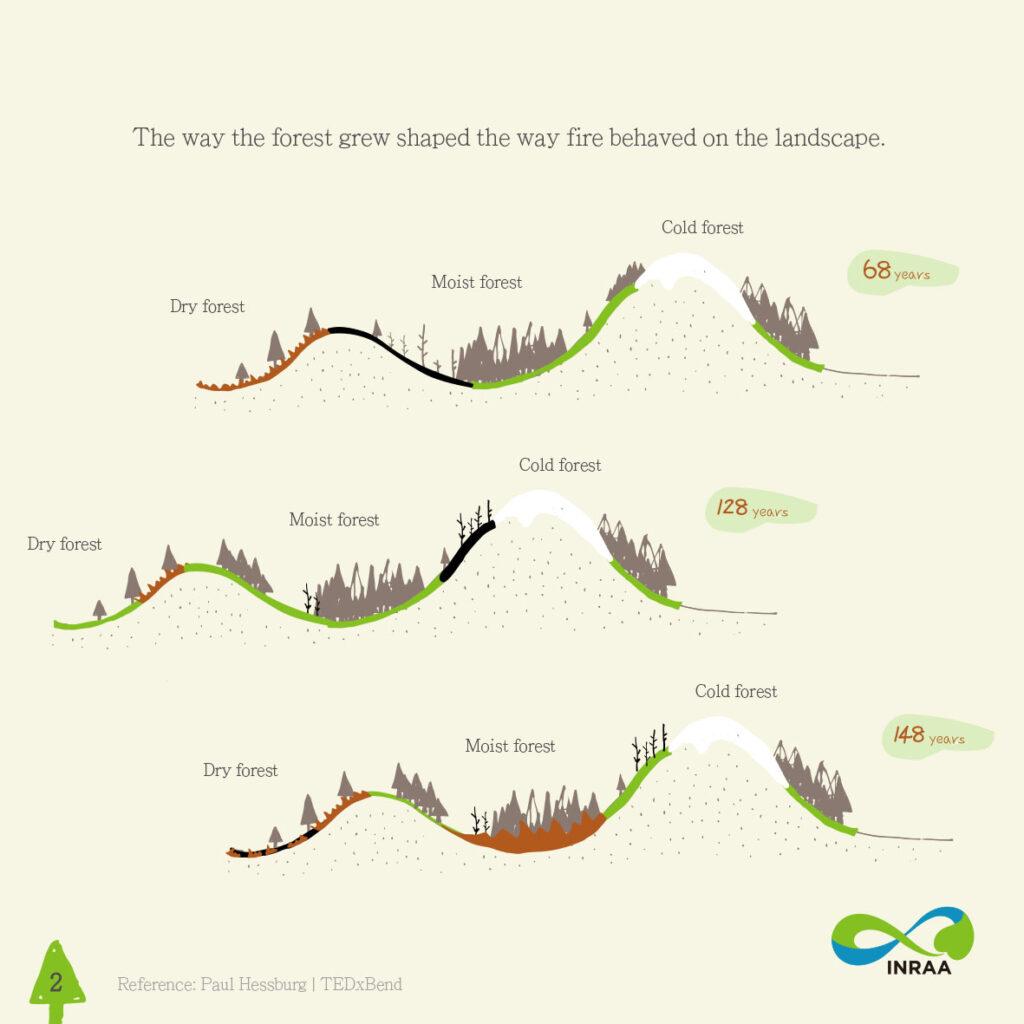

The way the forest grew shaped the way fire behaved on the landscape. You can see the new dry forest. Trees were open grown and fairly far apart. Fires were frequent here, and when they occurred, they weren’t that severe, while further up the mountain, in the moist and the cold forests, trees were more densely grown and fires were less frequent, but when they occurred, they were quite a bit more severe. These different forest types, the environments that they grew in and fire severity — they all worked together to shape this historical patchwork. And there was so much power in this patchwork. It provided a natural mechanism to resist the spread of future fires across the landscape. Once a patch of forest burned, it helped to prevent the flow of fire across the landscape. A way to think about it is, the burned patches helped the rest of the forest to be forest.

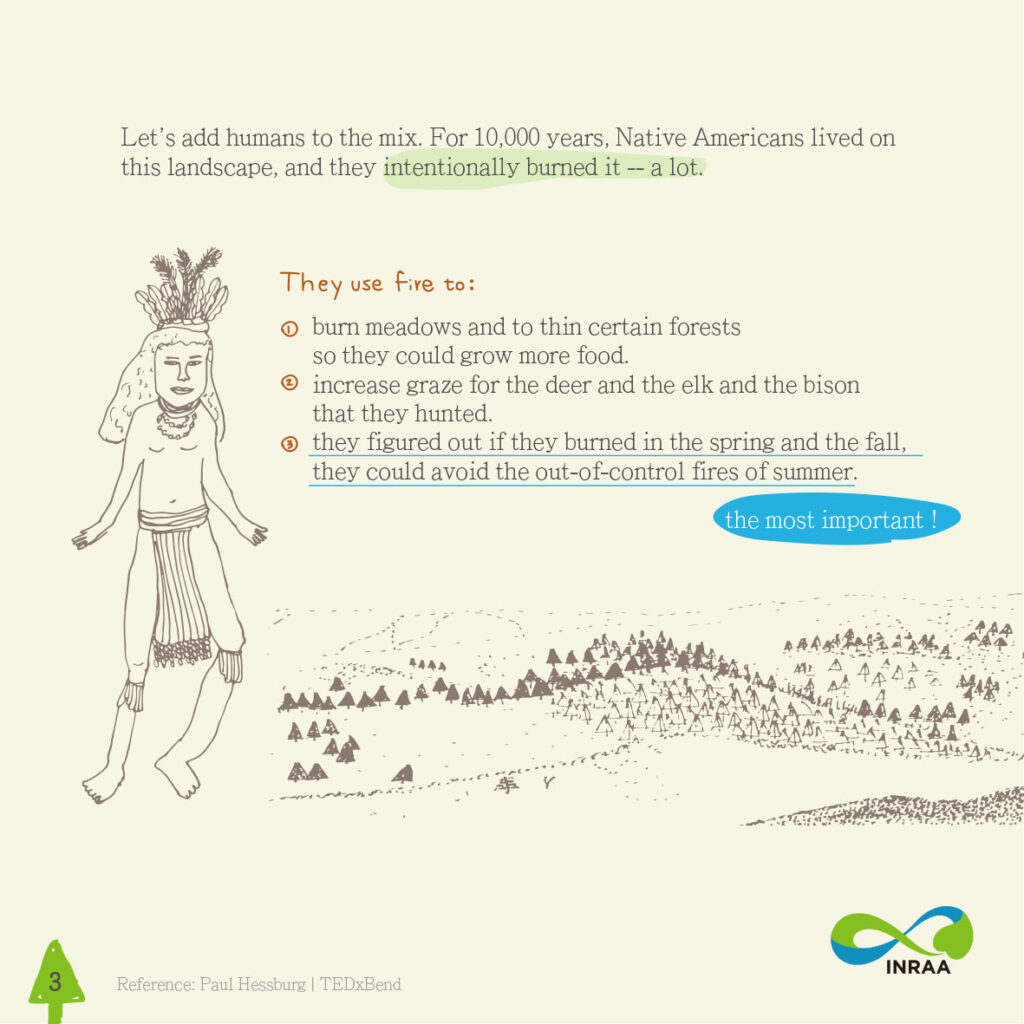

Let’s add humans to the mix. For 10,000 years, Native Americans lived on this landscape, and they intentionally burned it — a lot. They used fire to burn meadows and to thin certain forests so they could grow more food. They used fire to increase graze for the deer and the elk and the bison that they hunted. And most importantly, they figured out if they burned in the spring and the fall, they could avoid the out-of-control fires of summer.

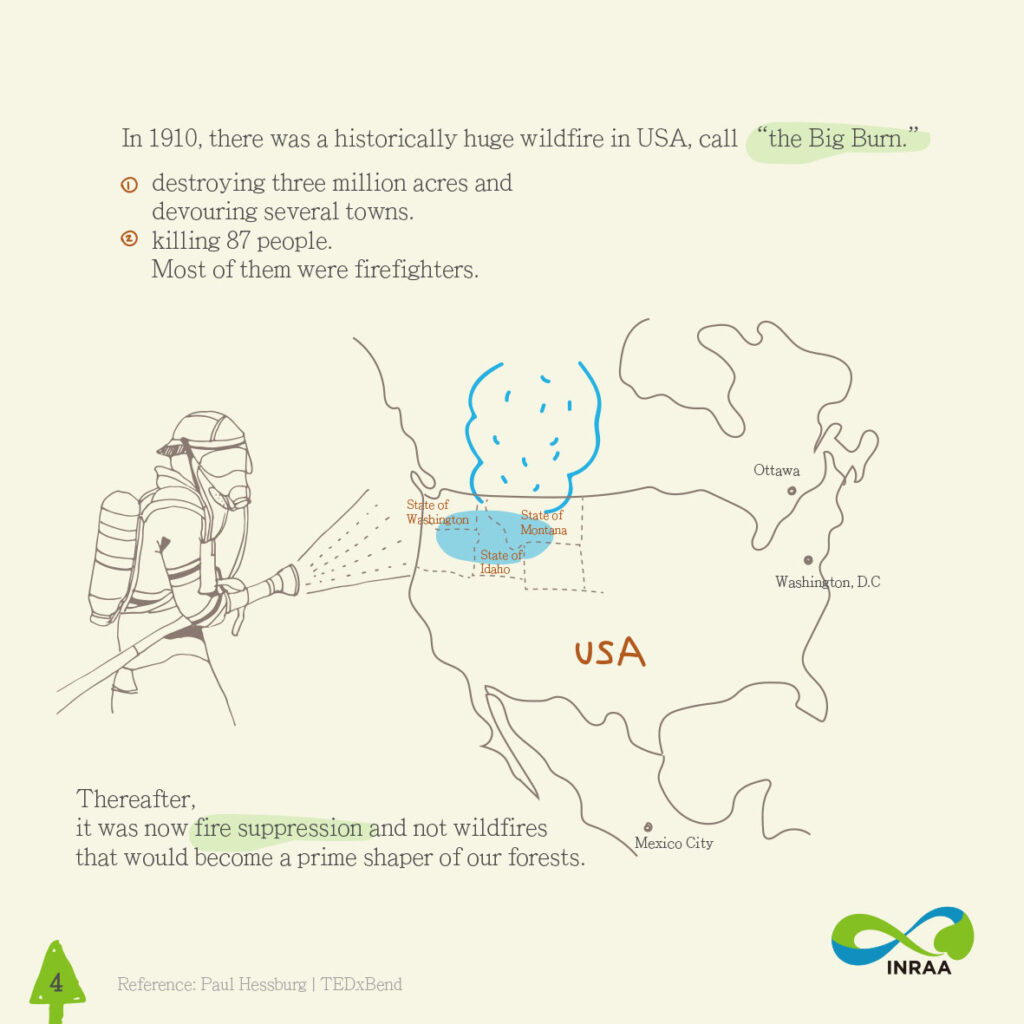

In 1910, we had a huge wildfire. It was the size of the state of Connecticut. We called it “the Big Burn.” It stretched from eastern Washington to western Montana, and it burned, in a few days, three million acres, devoured several towns, and it killed 87 people. Most of them were firefighters.

Because of the Big Burn, wildfire became public enemy number one, and this would shape the way that we would think about wildfire in our society for the next hundred years. Thereafter, the Forest Service, just five years young at the time, was tasked with the responsibility of putting out all wildfires on 193 million acres of public lands, and they took this responsibility very seriously. They developed this unequaled ability to put fires out, and they put out 95 to 98 percent of all fires every single year in the US. And from this point on, it was now fire suppression and not wildfires that would become a prime shaper of our forests.

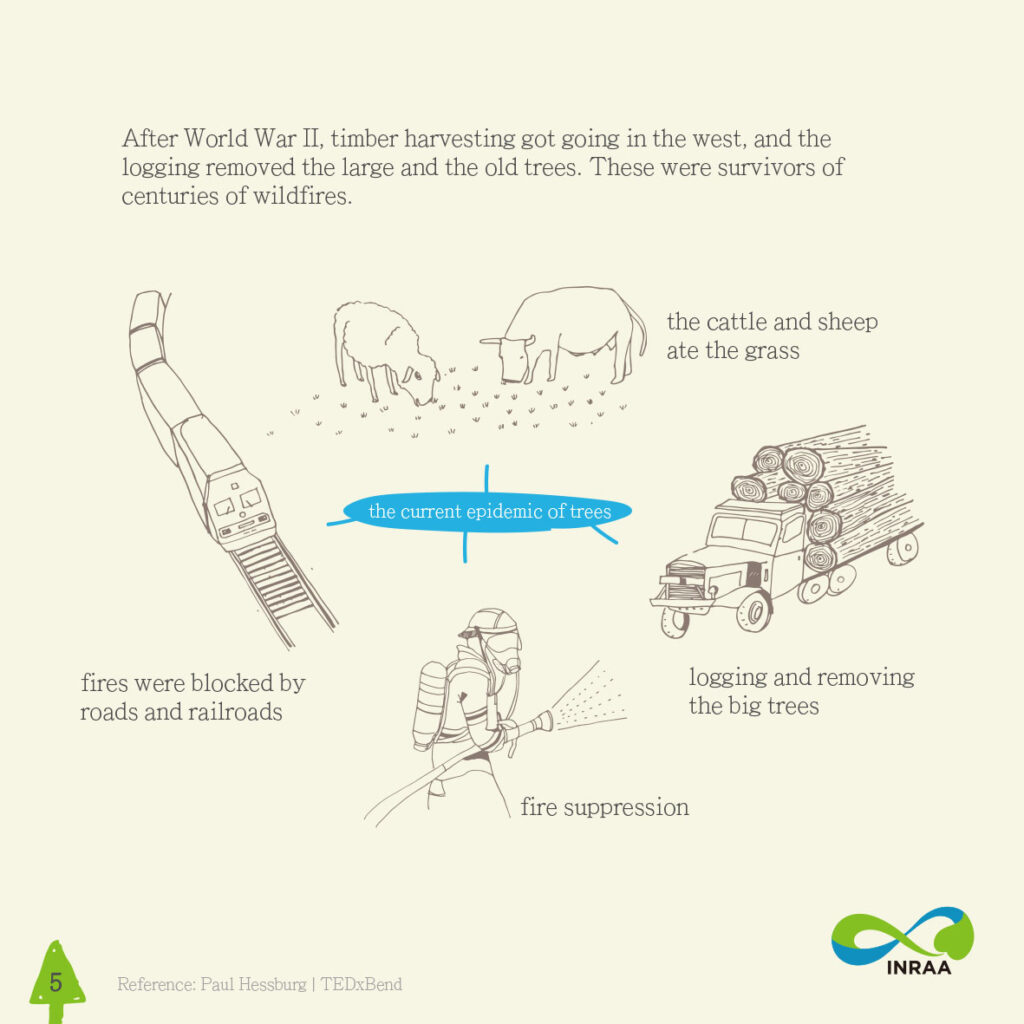

After World War II, timber harvesting got going in the west, and the logging removed the large and the old trees. These were survivors of centuries of wildfires. And the forest filled in. Thin-barked, fire-sensitive small trees filled in the gaps, and our forests became dense, with trees so layered and close together that they were touching each other.

So fires were unintentionally blocked by roads and railroads, the cattle and sheep ate the grass, then along comes fire suppression and logging, removing the big trees, and you know what happened? All these factors worked together to allow the forest to fill in, creating what I call the current epidemic of trees.

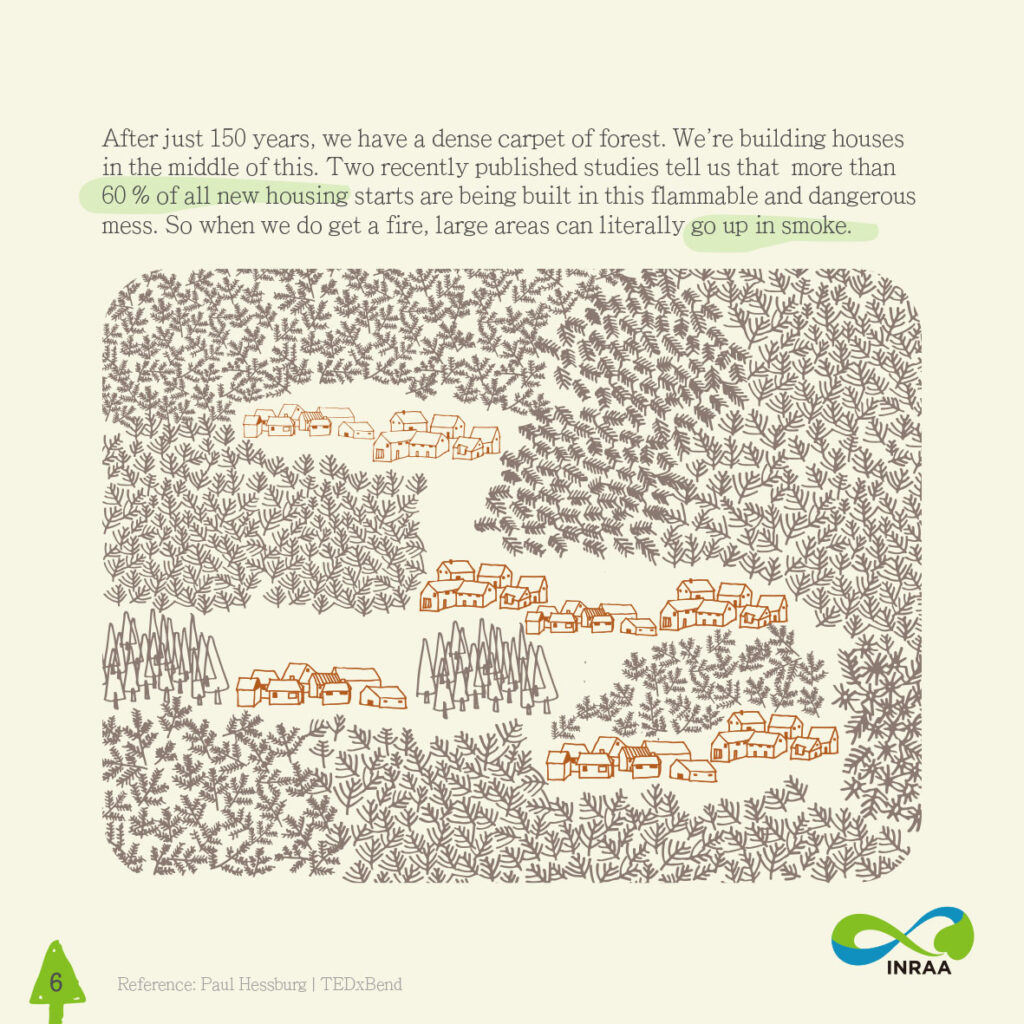

When you compare what forests looked like 100 years ago and today, the change is actually remarkable. After just 150 years, we have a dense carpet of forest.

But there’s more. Because trees are growing so close together, and because tree species, tree sizes and ages are so similar across large areas, fires not only move easily from acre to acre, but now, so do diseases and insect outbreaks, which are killing or reducing the vitality of really large sections of forest now. And after a century without fire, dead branches and downed trees on the forest floor, they’re at powder-keg levels.

What’s more, our summers are getting hotter and they’re getting drier and they’re getting windier. And the fire season is now 40 to 80 days longer each year. Because of this, climatologists are predicting that the area burned since 2000 will double or triple in the next three decades.

And we’re building houses in the middle of this. Two recently published studies tell us that more than 60 percent of all new housing starts are being built in this flammable and dangerous mess. So when we do get a fire, large areas can literally go up in smoke.

What do we do? We need to restore the power of the patchwork. We need to put the right kind of fire back into the system again. It’s how we can resize the severity of many of our future fires. And the silver lining is that we have tools and we have know-how to do this.

We can use prescribed burning to intentionally thin out trees and burn up dead fuels. We do this to systematically reduce them and keep them reduced. And what is that going to do? It’s going to create already-burned patches on the landscape that will resist the flow of future fires.

Also, there’s managed wildfires. Instead of putting all the fires out, we need to put some of them back to work thinning forests and reducing dead fuels. We can herd them around the landscape when it’s appropriate to do so to help restore the power of the patchwork. Last but not least, we can spread this message to our lawmakers and folks who can help us manage our fires and our forests